INTERVIEW: HOWARD GARDNER

By Christopher Koch

According to this Harvard psychologist's theory of multiple intelligences, it takes more than a high IQ to be a smart manager and leader.

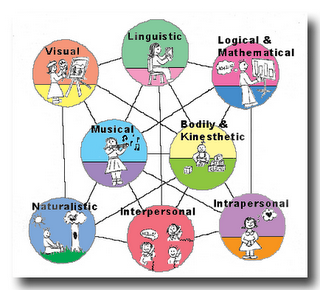

When Michael Jordan performs an inexplicable maneuver in the air above a basketball court or Luciano Pavarotti extracts another shimmering high C from the gristle of his vocal chords, we don't necessarily think of either of these men as being intelligent. They might be, but we assume these talents to be peripheral to intelligence rather than proof of it. Howard Gardner, a Harvard University professor of education and author, disagrees. When Jordan lifts off or Pavarotti opens wide, Gardner sees intelligence-something called bodily kinesthetic intelligence in the case of Jordan and musical intelligence in that of the big tenor. Gardner doesn't limit smarts to the traditional realms of logical reasoning and the ability to manipulate words and numbers. He says we are all endowed with eight distinct forms of intelligence that are genetically determined but can be enhanced through practice and learning.

Besides the physical and musical varieties, Gardner has identified six other types of intelligences: spatial (visual), interpersonal (the ability to understand others), intrapersonal (the ability to understand oneself), naturalist (the ability to recognize fine distinctions and patterns in the natural world) and, finally-the ones we worked so hard on in school-logical and linguistic.

Though Gardner's theory (first espoused in his 1983 book, Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences [Basic Books]), is often dismissed by the research community as little more than speculation, it has caught fire among educators, especially at the grade-school level. According to Gardner, children who don't excel in the "traditional" intelligences may not get the support they need. Kids who can brilliantly divine the feelings and motives of their sandbox mates, for example, won't really have an officially sanctioned chance to shine until they take a sales job or stumble into a college psychology class.

Gardner says this tendency to focus on traditional interpretations of intelligence carries over into the workplace, where employees who are excellent team players or who are adept at spatial reasoning (visualization) still risk getting fired if they can't write a decent memo. Similarly, the "smartest" Ivy League grads risk spectacular failure if employers assume that grade-point averages necessarily translate into leadership skills. In a recent interview with Senior Writer Christopher Koch, Gardner offered ways to help bring out the specific strengths of employees and company leaders.

CIO: Why has intelligence traditionally been limited to logical reasoning and the manipulation of words and numbers?

GARDNER: I think it has to do with the circumstances under which the intelligence test was developed. It was developed to predict who would have trouble in school. So it's basically a scholastic kind of measure, and the more you try to apply intelligence test results to milieus like schools-which can include certain kinds of professional or business organizations-the more appropriate the IQ test is, and the more appropriate that standard definition is. But once you go outside of school-like settings, then the standard theory of intelligence is much less appropriate. I often find that entrepreneurs think my theory is great. My interpretation is that they are people who weren't considered that smart in school because they didn't have good notation skills-you know, moving little symbols around. But they realize that often they were understanding things that other people, including their teachers, weren't understanding.

CIO: Traditional intelligence theories say there is a sort of reservoir of "mental energy" underlying all intellectual activities that constitutes the person's overall level of intelligence. Do you think this exists, or is it compartmentalized, as your theory seems to suggest?

GARDNER: I believe that the brain has evolved over millions of years to be responsive to different kinds of content in the world. Language content, musical content, spatial content, numerical content, etc. And all of us have computers that respond to those kinds of contents. But the strength or weakness of one computer doesn't particularly correlate with the other computer. If I know you're very good in music, I can predict with just about zero accuracy whether you're going to be good or bad in other things. So the notion of an undirected mental energy I think is not consistent with the data. It may be that some people have somewhat more efficiently running machines and perhaps, in general, they may learn or perform somewhat more rapidly than others. But being fast and not very spatial doesn't make you any better in spatial kinds of things; you probably just get the wrong answer more quickly. It's funny that artificial intelligence is ahead of psychology in this regard. Twenty-five years ago, the notion was you could create a general problem-solver software that could solve problems in many different domains. That just turned out to be totally wrong. So they began to develop expert systems. And expert systems have a lot of knowledge built in. An expert system for diagnosing disease is very different from an expert system to analyze chemical assays. And you can't do either unless you know a lot about the particular content that you're working with. So while most psychologists still think there's such a thing as general intelligence, no software designer would proceed on that basis.

CIO: You define the ability to interact successfully with other people as intelligence. Does this imply that this is an innate ability or something that can be learned?

GARDNER: I align myself with almost all researchers in assuming that anything we do is a composite of whatever genetic limitations were given to us by our parents and whatever kinds of environmental opportunities are available. You can have the best genes in the world, but if you're not exposed to music, you won't do anything in music. Conversely, you might have a meager endowment in a certain area, but if you spend a lot of time working on it, and your instructors are very ingenious in helping you, you might end up performing quite well.

CIO: What qualities constitute an "intelligent" executive?

GARDNER: First of all, I think there's more than one kind of intelligent executive. And in terms of my theory, I think there are some executives who are tremendously good planners and have a very good understanding of the organization with which they're working as well as the domain in which the organization works and how that domain, or field, is evolving. Other executives have more of the Ronald Reagan style. They are probably not good at planning or crunching numbers, but they're terrific at getting people to support a change in direction even if it means making some kind of a sacrifice. And ideally you get a chief executive who's strong in all of those areas as well as some I haven't mentioned. Probably the most important thing in a company is to be aware of dimensions like this and make sure that somehow they're represented in the leadership and that people aren't at cross purposes with one another. You don't want the person who's good at numbers proceeding in a very different direction than a person who's very good at long-term vision or the person who's very good at convincing people to join the team.

CIO: So the issue of collaboration becomes paramount?

GARDNER: Yeah. I think what I'm talking about really is an executive function. There are various executive functions, and if they exist in one individual it's more likely that the company will be able to work in a harmonious way than if they happen to exist in different people in different units. If they exist in different people in different units, then it becomes a major undertaking to make sure they can work well together. And that's a strong argument for having management teams with some kind of longevity because it takes time to develop good working relationships. The notion that you can drop Mr. A and hire Miss B from another company and have her slot right in is unrealistic. A lot of knowledge in any kind of an organization is what we call task knowledge. These are things that people who have been there a long time understand are important, but they may not know how to talk about them. It's often called the culture of the organization. And if you've been in an organization for a while, you've picked up the culture; and if it doesn't take, you probably aren't going to stay with that organization. But that's not something that can be instantly acquired.

CIO: You mention that cultures affect intelligence. For example, some tribes value musical ability as a bonding and historical mechanism. What role does a corporate culture play in improving peoples' intelligence?

GARDNER: I think corporate culture can either stunt it or enhance it, and a lot depends on the assumptions made by the leadership about how much growth is possible in people and how much opportunity to give people to learn and to fail. I think tolerating a certain degree of failure-not because it's good for you but because it's a necessary part of growth-is a very important part of the message the leadership can give. My theory of multiple intelligences has influenced a lot about how I think about the workplace. Fifteen or 20 years ago when I was hiring people, I often said to myself even if I wasn't aware of it, "How much is this person like me?" Either that person should be like me or I should try to make that person be like me. And now my attitude is very much the opposite. We should be looking for people who aren't like me, who have strengths that complement mine. Especially with teams, I don't say, 'Are these people all the same?' I say, 'In what ways can they achieve more working together than if you simply put them together randomly or if you simply assumed that any two people would be able to handle things reasonably well?' So I think the culture that's created over time by the people who have an authorized leadership position or an unauthorized leadership role has tremendous implication for whether people actually do become more intelligent on the job.

CIO: The IS executive has been at a kind of leadership crossroads for a while. In most companies the IS role has traditionally been a very functional, managerial-style role, and now the CIO is becoming one of the overall executive-level business chieftains.

GARDNER: There are two types of leadership, I believe. One type is indirect leadership, where the power to influence comes not from the individual but from something he or she has done. The second type is direct leadership, whereby someone goes out publicly and tells the company and the world, "This is what we're about, this is our goal, these are the obstacles, this is how we're going to achieve it. And by the way, if you look at how I am, that's the best indication of how you should be, too." If you're an expert, and you work with other experts, you can assume people are schooled, and you can be quite technical and have a complicated story. If you're talking to the wider world, then you have to assume a mind that's unschooled, and your story has to be much simpler, much more elemental.

CIO: Your description of direct and indirect leadership suggests that IS leaders are teetering between the two types of leadership. How can they deal with this precarious role?

GARDNER: The most important thing is not to confuse when you're wearing one hat with when you're wearing the other. [Former British Prime Minister] Margaret Thatcher is my best example of that. She was quite sophisticated. She could sit down with ministers and talk shop, but when she went on television she never talked that way. She spoke in plain English, with common sense, and she was therefore able to be effective in both spheres. Reagan didn't have the problem because he didn't have much of a technocratic expertise. He spoke to the unschooled mind universally. But you have leaders in America-[Former Governor of Massachusetts Michael] Dukakis was an example-who don't understand that what works well with people who are sophisticated isn't going to work well with people who don't have the kind of training. So you have to become bilingual. Not just bilingual but "bisymbolic," because the symbols you use in dealing with your colleagues-whether they're graphical, numeric or linguistic-they're the language of the discipline, of the trade, of the professional school. The other thing is when you are working with your peers, especially in the information world, they're looking for innovation, and that doesn't frighten them at all. In fact, the kudos are for people who can come up with new ideas. That's not what works best in a more public environment where people are often afraid of something that sounds too new. People want things to change, but they don't want it to come crashing down on them. The other thing I talk about in the book Leading Minds: An Anatomy of Leadership, [Basic Books, 1995] is the relationship between reflection and public confrontation. Creators spend most of their time reflecting by themselves or with a few other people. About 10 percent of the time they go public to see whether what they're saying makes sense. I think the ratio is approximately reversed for people who are leaders.

CIO: Does that mean that the primary intelligence that a leader should have is interpersonal, or are there others?

GARDNER: Well, if storytelling is important, then your narrative ability, or your ability to put into words or use what someone else has put into words effectively, is important too. In fact, at the end of Leading Minds I talk about the linguistic intelligences and the personal intelligences as sort of the sine qua non of leadership. It doesn't mean that all leaders have to start with having well-developed variants of both of them, but if they're not a particularly good speaker or they don't have a particularly good understanding of other people, that's got to be a top priority for them.

CIO: For adults and businesses, this theory seems to portend the same sorts of things that Myers-Briggs and other personality tests do: that it can be used to help staff teams with diverse types. What other implications does this have for running a department or a project?

GARDNER: It's not just putting together a good team; it's matching a person with tasks. A trickier thing is when somebody's job changes for whatever reason. You then have to ask yourself the question, "Do the person's current skills match the job?" If not, how can we best use the intelligences they have as well as the ones that other people who work with them have to do this new job better. So you need to have what I would call a good mental model of the abilities and lack of abilities of people, and a good mental model of the job. And as the job evolves, it's kind of dynamic-you have to think about how people's abilities can be rearranged or stretched or reconfigured or combined with other people's. I think the whole notion of "intrapersonal" intelligence is getting more and more important all the time in business. It's not just knowing yourself but having other people at work think a lot about themselves and about how they can use their abilities maximally. So often the difference between success and failure is not taking 100 courses to sharpen your skills but rather figuring out how, given your abilities, you can adjust yourself to a kind of requirement. And because historically that has been ruled as taboo-you don't want to talk about your inner feelings and thoughts and so on-I think there's a missed opportunity for people to mobilize themselves.

All readers are recommended to view this site relate to this entry:

http://www.cio.com/archive/031596_qa.html

According to this Harvard psychologist's theory of multiple intelligences, it takes more than a high IQ to be a smart manager and leader.

When Michael Jordan performs an inexplicable maneuver in the air above a basketball court or Luciano Pavarotti extracts another shimmering high C from the gristle of his vocal chords, we don't necessarily think of either of these men as being intelligent. They might be, but we assume these talents to be peripheral to intelligence rather than proof of it. Howard Gardner, a Harvard University professor of education and author, disagrees. When Jordan lifts off or Pavarotti opens wide, Gardner sees intelligence-something called bodily kinesthetic intelligence in the case of Jordan and musical intelligence in that of the big tenor. Gardner doesn't limit smarts to the traditional realms of logical reasoning and the ability to manipulate words and numbers. He says we are all endowed with eight distinct forms of intelligence that are genetically determined but can be enhanced through practice and learning.

Besides the physical and musical varieties, Gardner has identified six other types of intelligences: spatial (visual), interpersonal (the ability to understand others), intrapersonal (the ability to understand oneself), naturalist (the ability to recognize fine distinctions and patterns in the natural world) and, finally-the ones we worked so hard on in school-logical and linguistic.

Though Gardner's theory (first espoused in his 1983 book, Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences [Basic Books]), is often dismissed by the research community as little more than speculation, it has caught fire among educators, especially at the grade-school level. According to Gardner, children who don't excel in the "traditional" intelligences may not get the support they need. Kids who can brilliantly divine the feelings and motives of their sandbox mates, for example, won't really have an officially sanctioned chance to shine until they take a sales job or stumble into a college psychology class.

Gardner says this tendency to focus on traditional interpretations of intelligence carries over into the workplace, where employees who are excellent team players or who are adept at spatial reasoning (visualization) still risk getting fired if they can't write a decent memo. Similarly, the "smartest" Ivy League grads risk spectacular failure if employers assume that grade-point averages necessarily translate into leadership skills. In a recent interview with Senior Writer Christopher Koch, Gardner offered ways to help bring out the specific strengths of employees and company leaders.

CIO: Why has intelligence traditionally been limited to logical reasoning and the manipulation of words and numbers?

GARDNER: I think it has to do with the circumstances under which the intelligence test was developed. It was developed to predict who would have trouble in school. So it's basically a scholastic kind of measure, and the more you try to apply intelligence test results to milieus like schools-which can include certain kinds of professional or business organizations-the more appropriate the IQ test is, and the more appropriate that standard definition is. But once you go outside of school-like settings, then the standard theory of intelligence is much less appropriate. I often find that entrepreneurs think my theory is great. My interpretation is that they are people who weren't considered that smart in school because they didn't have good notation skills-you know, moving little symbols around. But they realize that often they were understanding things that other people, including their teachers, weren't understanding.

CIO: Traditional intelligence theories say there is a sort of reservoir of "mental energy" underlying all intellectual activities that constitutes the person's overall level of intelligence. Do you think this exists, or is it compartmentalized, as your theory seems to suggest?

GARDNER: I believe that the brain has evolved over millions of years to be responsive to different kinds of content in the world. Language content, musical content, spatial content, numerical content, etc. And all of us have computers that respond to those kinds of contents. But the strength or weakness of one computer doesn't particularly correlate with the other computer. If I know you're very good in music, I can predict with just about zero accuracy whether you're going to be good or bad in other things. So the notion of an undirected mental energy I think is not consistent with the data. It may be that some people have somewhat more efficiently running machines and perhaps, in general, they may learn or perform somewhat more rapidly than others. But being fast and not very spatial doesn't make you any better in spatial kinds of things; you probably just get the wrong answer more quickly. It's funny that artificial intelligence is ahead of psychology in this regard. Twenty-five years ago, the notion was you could create a general problem-solver software that could solve problems in many different domains. That just turned out to be totally wrong. So they began to develop expert systems. And expert systems have a lot of knowledge built in. An expert system for diagnosing disease is very different from an expert system to analyze chemical assays. And you can't do either unless you know a lot about the particular content that you're working with. So while most psychologists still think there's such a thing as general intelligence, no software designer would proceed on that basis.

CIO: You define the ability to interact successfully with other people as intelligence. Does this imply that this is an innate ability or something that can be learned?

GARDNER: I align myself with almost all researchers in assuming that anything we do is a composite of whatever genetic limitations were given to us by our parents and whatever kinds of environmental opportunities are available. You can have the best genes in the world, but if you're not exposed to music, you won't do anything in music. Conversely, you might have a meager endowment in a certain area, but if you spend a lot of time working on it, and your instructors are very ingenious in helping you, you might end up performing quite well.

CIO: What qualities constitute an "intelligent" executive?

GARDNER: First of all, I think there's more than one kind of intelligent executive. And in terms of my theory, I think there are some executives who are tremendously good planners and have a very good understanding of the organization with which they're working as well as the domain in which the organization works and how that domain, or field, is evolving. Other executives have more of the Ronald Reagan style. They are probably not good at planning or crunching numbers, but they're terrific at getting people to support a change in direction even if it means making some kind of a sacrifice. And ideally you get a chief executive who's strong in all of those areas as well as some I haven't mentioned. Probably the most important thing in a company is to be aware of dimensions like this and make sure that somehow they're represented in the leadership and that people aren't at cross purposes with one another. You don't want the person who's good at numbers proceeding in a very different direction than a person who's very good at long-term vision or the person who's very good at convincing people to join the team.

CIO: So the issue of collaboration becomes paramount?

GARDNER: Yeah. I think what I'm talking about really is an executive function. There are various executive functions, and if they exist in one individual it's more likely that the company will be able to work in a harmonious way than if they happen to exist in different people in different units. If they exist in different people in different units, then it becomes a major undertaking to make sure they can work well together. And that's a strong argument for having management teams with some kind of longevity because it takes time to develop good working relationships. The notion that you can drop Mr. A and hire Miss B from another company and have her slot right in is unrealistic. A lot of knowledge in any kind of an organization is what we call task knowledge. These are things that people who have been there a long time understand are important, but they may not know how to talk about them. It's often called the culture of the organization. And if you've been in an organization for a while, you've picked up the culture; and if it doesn't take, you probably aren't going to stay with that organization. But that's not something that can be instantly acquired.

CIO: You mention that cultures affect intelligence. For example, some tribes value musical ability as a bonding and historical mechanism. What role does a corporate culture play in improving peoples' intelligence?

GARDNER: I think corporate culture can either stunt it or enhance it, and a lot depends on the assumptions made by the leadership about how much growth is possible in people and how much opportunity to give people to learn and to fail. I think tolerating a certain degree of failure-not because it's good for you but because it's a necessary part of growth-is a very important part of the message the leadership can give. My theory of multiple intelligences has influenced a lot about how I think about the workplace. Fifteen or 20 years ago when I was hiring people, I often said to myself even if I wasn't aware of it, "How much is this person like me?" Either that person should be like me or I should try to make that person be like me. And now my attitude is very much the opposite. We should be looking for people who aren't like me, who have strengths that complement mine. Especially with teams, I don't say, 'Are these people all the same?' I say, 'In what ways can they achieve more working together than if you simply put them together randomly or if you simply assumed that any two people would be able to handle things reasonably well?' So I think the culture that's created over time by the people who have an authorized leadership position or an unauthorized leadership role has tremendous implication for whether people actually do become more intelligent on the job.

CIO: The IS executive has been at a kind of leadership crossroads for a while. In most companies the IS role has traditionally been a very functional, managerial-style role, and now the CIO is becoming one of the overall executive-level business chieftains.

GARDNER: There are two types of leadership, I believe. One type is indirect leadership, where the power to influence comes not from the individual but from something he or she has done. The second type is direct leadership, whereby someone goes out publicly and tells the company and the world, "This is what we're about, this is our goal, these are the obstacles, this is how we're going to achieve it. And by the way, if you look at how I am, that's the best indication of how you should be, too." If you're an expert, and you work with other experts, you can assume people are schooled, and you can be quite technical and have a complicated story. If you're talking to the wider world, then you have to assume a mind that's unschooled, and your story has to be much simpler, much more elemental.

CIO: Your description of direct and indirect leadership suggests that IS leaders are teetering between the two types of leadership. How can they deal with this precarious role?

GARDNER: The most important thing is not to confuse when you're wearing one hat with when you're wearing the other. [Former British Prime Minister] Margaret Thatcher is my best example of that. She was quite sophisticated. She could sit down with ministers and talk shop, but when she went on television she never talked that way. She spoke in plain English, with common sense, and she was therefore able to be effective in both spheres. Reagan didn't have the problem because he didn't have much of a technocratic expertise. He spoke to the unschooled mind universally. But you have leaders in America-[Former Governor of Massachusetts Michael] Dukakis was an example-who don't understand that what works well with people who are sophisticated isn't going to work well with people who don't have the kind of training. So you have to become bilingual. Not just bilingual but "bisymbolic," because the symbols you use in dealing with your colleagues-whether they're graphical, numeric or linguistic-they're the language of the discipline, of the trade, of the professional school. The other thing is when you are working with your peers, especially in the information world, they're looking for innovation, and that doesn't frighten them at all. In fact, the kudos are for people who can come up with new ideas. That's not what works best in a more public environment where people are often afraid of something that sounds too new. People want things to change, but they don't want it to come crashing down on them. The other thing I talk about in the book Leading Minds: An Anatomy of Leadership, [Basic Books, 1995] is the relationship between reflection and public confrontation. Creators spend most of their time reflecting by themselves or with a few other people. About 10 percent of the time they go public to see whether what they're saying makes sense. I think the ratio is approximately reversed for people who are leaders.

CIO: Does that mean that the primary intelligence that a leader should have is interpersonal, or are there others?

GARDNER: Well, if storytelling is important, then your narrative ability, or your ability to put into words or use what someone else has put into words effectively, is important too. In fact, at the end of Leading Minds I talk about the linguistic intelligences and the personal intelligences as sort of the sine qua non of leadership. It doesn't mean that all leaders have to start with having well-developed variants of both of them, but if they're not a particularly good speaker or they don't have a particularly good understanding of other people, that's got to be a top priority for them.

CIO: For adults and businesses, this theory seems to portend the same sorts of things that Myers-Briggs and other personality tests do: that it can be used to help staff teams with diverse types. What other implications does this have for running a department or a project?

GARDNER: It's not just putting together a good team; it's matching a person with tasks. A trickier thing is when somebody's job changes for whatever reason. You then have to ask yourself the question, "Do the person's current skills match the job?" If not, how can we best use the intelligences they have as well as the ones that other people who work with them have to do this new job better. So you need to have what I would call a good mental model of the abilities and lack of abilities of people, and a good mental model of the job. And as the job evolves, it's kind of dynamic-you have to think about how people's abilities can be rearranged or stretched or reconfigured or combined with other people's. I think the whole notion of "intrapersonal" intelligence is getting more and more important all the time in business. It's not just knowing yourself but having other people at work think a lot about themselves and about how they can use their abilities maximally. So often the difference between success and failure is not taking 100 courses to sharpen your skills but rather figuring out how, given your abilities, you can adjust yourself to a kind of requirement. And because historically that has been ruled as taboo-you don't want to talk about your inner feelings and thoughts and so on-I think there's a missed opportunity for people to mobilize themselves.

All readers are recommended to view this site relate to this entry:

http://www.cio.com/archive/031596_qa.html

0 comments:

Post a Comment